Slack’s Incident on 2-22-22 Reading Note

Why reading incident report is interesting?

We can learn many things from an incident report, such as how to react to an incident, review architecture, and analyze problems in a real case.

Have to say, it is much more enjoyable to learn from others’ incident report.

Affect

On February 22, 2022 from 6:00 AM PST to 9:14 AM PST, some customers can’t access Slack[2].

Rough Timeline

- received user tickets

- received alarms

- detected database suffers higher load than usual

- query timeout, DB overloaded

- decreased the requests acceptance rate => DB back to normal

- increased the rate => DB overloaded again

- decreased the rate => back to normal => increase by small steps

The Architecture

The backend server will query the cache first, if the cache missed, query the DB.

v = get(k)

if v is nil {

v = fetch from DB

set(k, v)

}

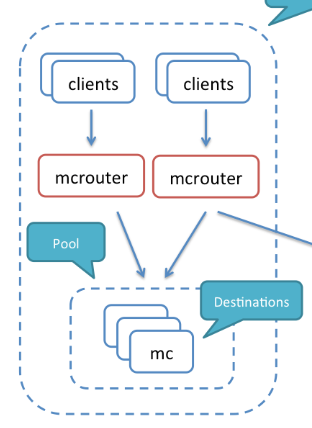

Clients(app servers) will send requests to the Mcrouter, then the Mcrouter will proxy the requests to Memcached nodes.

Consul is used for discovering Memcached nodes. And mcrib will watch Consul for getting alive Memcached nodes.

Then the info will be used by mcrouter for selecting memcached nodes.

When the agent(Consul) restart occurs on a memcached node, the node that leaves the service catalog gets replaced by Mcrib. The new cache node will be empty.

I’m not really understand this sentence.

It seems that the consul agent will be deployed on some Memcached nodes, and when the Cousul agent restarts, the Memcached node will be replaced by a new empty node.

What happened

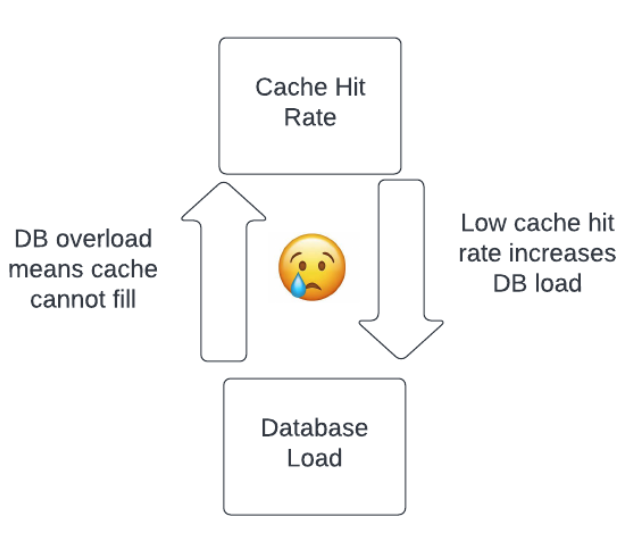

Cache failure causes hit rate to decrease

Upgrade Consul agent => memcached nodes are replaced by empty nodes => cache hit decreased

Cache failure => DB heavy read load + read amplification => DB overload

A Cache can reduce a lot of loads for DB. When cache failure happens, DB will suffer much more load than usual.

For Slack, one function/API needs to query many DB shards as it is not sharded well.

Those caused the DB to be overloaded.

Cascading failure

Then cascading failure happened.

Thinking in general

Instead of focusing on the incident closely we can make the problem more general and see what we can learn from previous experiences.

Cache failure

After we add a cache layer it will have two effects: speed up requests and reduce DB read load[4].

Most applications are read-heavy, for example in Facebook, they have two orders of magnitude more reads than writes[3].

Another fact is cache is much faster say 10 times than DB usually.

So if the cache crashed, DB will suffer a really heavy load most time. That means we need to take cache failure seriously.

For caching, Facebook has published a paper[3] about how they design their cache system and make it available all the time.

High availability

For achieving high availability, we need to ask “what happens if it fails?”[8].

The system may get stuck(livelock[6]) or crash(cascading failure) by any component failure.

We have two options, fix all potential issues or make the system recover fastly.

Options one is infeasible because there are too many components and too many potential issues.

But we can achieve fast recovery, that coverts unspecific problems into specific ones.

For Google GFS[7], they think “component failures are the norm rather than the exception.”, and they handle availability problems through fast recovery and replication.

Overload control

Most problems are caused by overload and most time the loads are not predictable.

To avoid such problems, we can design some mechanisms to protect our systems.

The most obvious way is rate-limiter, it sets a hard value and if throughput is over the value, the rate-limter will drop the over-part.

One inconvenience of the rate-limiter is we need to change it manually, as we can see in this incident.

Microservices have complexity dependency whose parts are dynamic changed(software upgrade, hardware config update, or something else), so it’s impossible to find a good value for all situations.

Netflix created concurrency-limits based on such observations.

Another thing we need to consider is how to provide the best experience for users when we start to drop their requests.

“Overload Control for Scaling WeChat Microservices”[5] has a good answer to this question.

In the paper, they drop requests based on features and users, and they use queue time to detect overload config the limit value dynamically.

References

- Slack’s Incident on 2-22-22 https://slack.engineering/slacks-incident-on-2-22-22/

- Slack status history https://status.slack.com/2022-02-22

- Scaling Memcache at Facebook at NSDI ‘13 https://www.usenix.org/conference/nsdi13/technical-sessions/presentation/nishtala

- MIT 6.824 Spring 2022 LEC 16 https://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.824/schedule.html

- Hao Zhou. Overload Control for Scaling WeChat Microservices, 2018

- J. C. Mogul and K. Ramakrishnan. Eliminating receive livelock in an interrupt-driven kernel. 1997.

- Sanjay Ghemawat. The Google File System 2003

- J Armstrong. A history of Erlang. 2007